Take-home points

|

|

Bios Dr. Bommakanti, Dr. Yu and Dr. Adams are first-year vitreoretinal surgery fellows at Wills Eye Hospital/Mid Atlantic Retina, Philadelphia. Dr. Yonekawa is an adult and pediatric retina specialist at Wills Eye Hospital/Mid Atlantic Retina. DISCLOSURES: Dr. Yonekawa is a consultant for Alcon, EyePoint Pharmaceuticals and Versant Health. The other authors have no relevant disclosures. |

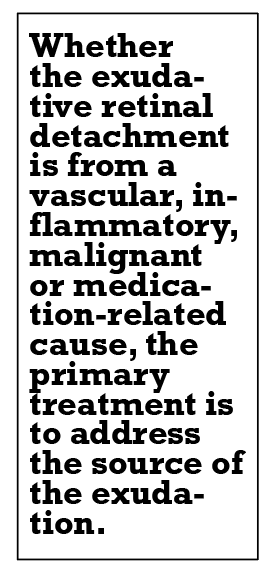

Caring for pediatric patients with retinal detachments often requires mindfulness because the presentation, etiology and treatment can be different than in adults. For example, pediatric rhegmatogenous RDs are more likely to be chronic and macula-involving. The posterior hyaloid is typically firmly adherent to the retina, and the detachments aren’t usually not caused by posterior vitreous detachment.

Proliferative vitreoretinopathy is common in children, and underlying developmental or systemic disease may be present.1,2 Here, we review how to care for pediatric patients with RDs, from initial evaluation through management and follow-up.

The initial evaluation

A thorough family and medical history, including birth history, are important in the initial evaluation. Get to know the family and make sure everyone is as comfortable as they can be during what is likely to be a stressful time.

Examining pediatric patients can have limitations. Even some adults have difficulty tolerating a careful, dilated fundus examination. What’s more, some children with RDs may have predisposing conditions such as self-injurious behavior that may limit the examination.3

Infants and very young children can often be held by their parents or trained staff during the examination. For older children, distracting them with a favorite toy or video may give you enough time for a focused examination to make the diagnosis. Again, their parents can be especially helpful here.

Ultra-widefield fundus imaging and B-scan ultrasonography can supplement the exam; they’re much more comfortable for the child than ophthalmoscopy. Remember, examining the fellow eye is critical because many pediatric patients with an RD in one eye can in fact have bilateral RDs. Indeed, the majority have some pathology in the fellow eye, such as lattice degeneration, high myopia or other congenital abnormalities.2 Ultimately, the threshold to proceed with an exam under anesthesia should be low if a sight-threatening pathology such as RD is on the differential and, of course, if there’s even a fleeting suspicion for retinoblastoma.

|

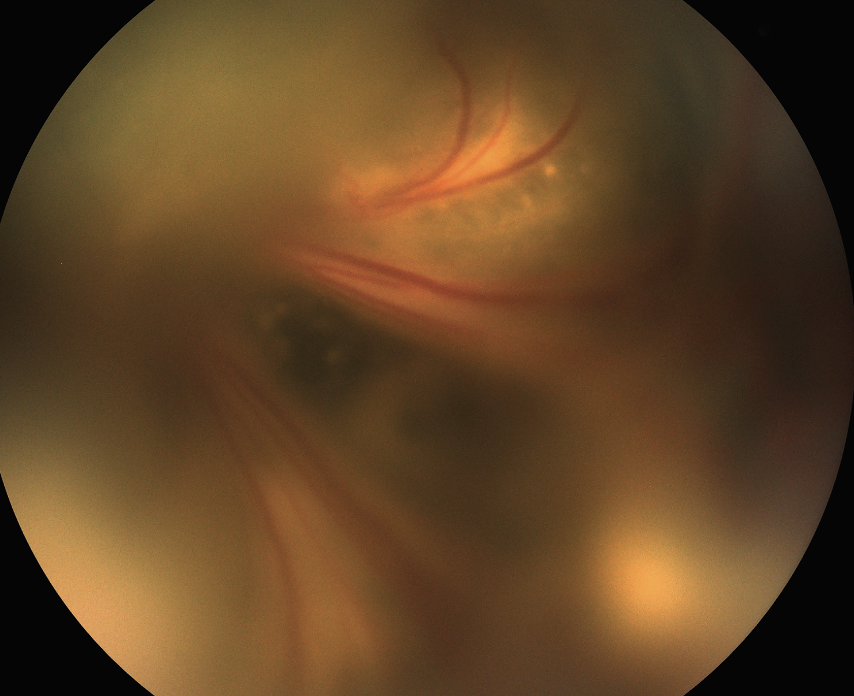

| Figure 1. A total tractional retinal detachment from familial exudative vitreoretinopathy (FEVR) from a FZD4 mutation. This is mostly a tractional retinal detachment, but with concurrent exudation. Lens-sparing vitrectomy was performed to dissect the hyaloidal membranes to reattach the posterior pole. |

Making the diagnosis

Determining whether the RD is primarily rhegmatogenous, tractional (TRD) or exudative (ERD) is important for planning and prognostication. Retinoblastoma must first and foremost be ruled out in any clinical scenario because a timely and accurate diagnosis can save the child’s life.

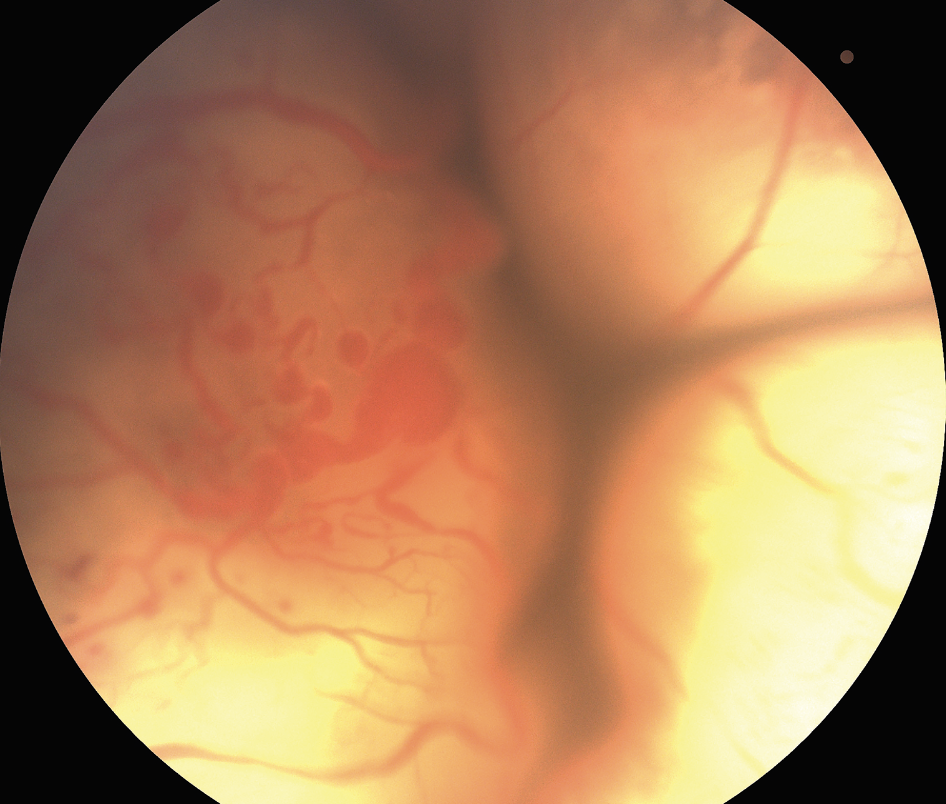

Risk factors for RRDs include trauma/retinal dialysis, high myopia, history of prematurity, X-linked retinoschisis, Stickler syndrome and Marfan syndrome. For TRDs they include persistent fetal vasculature (PFV), familial exudative vitreoretinopathy (FEVR, Figure 1) and retinopathy of prematurity. ERD risk factors include Coats’ disease (Figure 2, below), uveitis and tumors. Note that many of the conditions, such as ROP and FEVR, can present with any combination of TRD/ERD/RRD.

|

| Figure 2. Total exudative retinal detachment from Coats’ disease. Note the extensive subretinal yellow exudates and the numerous vascular abnormalities include light bulb aneurysms. Anterior chamber infusion with external drainage was performed with subsequent perfluorooctane injection and endolaser treatment. |

Surgical techniques and considerations

Some RRDs can be effectively treated with laser retinopexy and some milder TRDs can be managed conservatively. ERDs should be treated by addressing the underlying pathology.

Other pediatric RRDs and TRDs, however, are usually best treated surgically. Important surgical considerations in pediatric patients include the different anatomy/physiology, a greater propensity for PVR if a retinal break is introduced and a potentially higher risk of anesthesia.

|

Rhegmatogenous retinal detachment

Scleral buckling is the best surgical approach for the vast majority of pediatric RRDs. The formed vitreous and adherent posterior hyaloid make vitrectomy challenging in pediatric eyes because the vitreous can’t be fully separated from the retina, a necessary step for vitrectomy to be effective for RRD repair.

On the other hand, the formed vitreous, lack of posterior vitreous detachment, and good retinal pigment epithelial pump function all increase the likelihood of a successful surgery with SB. The approach usually doesn’t require positioning and has a significantly lower risk for intraocular complications and endophthalmitis.

|

For these reasons, SB makes the most sense in children, particularly if compliance is limited in younger children or those with developmental delay.3 However, a national database analysis found that despite SB having the highest single surgery success rate, it was only performed in 32 percent of eyes treated with incisional surgery in the United States.4 This is a concerning trend that we need to reverse.

Traction retinal detachment

The three most important principles of TRD surgery in children are:

- Release the traction.

- Don’t make any iatrogenic breaks

- Allow the RPE to pump the fluid out.

Unlike adult TRDs, pediatric TRDs, such as in ROP and FEVR, can’t be flattened completely at the end of the case. Iatrogenic breaks, including intentional retinotomies and retinectomies, can result in relentless PVR. The best approach is to release the traction using the vitreous cutter or additional instrumentation, get out of the eye and wait for the RPE to pump the fluid out.

Exudative retinal detachment

Whether the ERD is from a vascular (the most common type), inflammatory, malignant or medication-related cause, the primary treatment is to address the source of the exudation.

For exudation from Coats’ disease, laser photocoagulation ablates the anomalous leaky vasculature, with or without adjunctive anti-VEGF agents and steroids. For exudation from retinoblastoma or choroidal hemangioma, treat the tumors. For exudation from uveitis, treat the inflammation. The mantra “no iatrogenic breaks” applies here also.

Anesthesia risk and immediate sequential bilateral surgery

|

Some pediatric vitreoretinopathies such as ROP can progress rapidly in both eyes. In most countries, including the United States, we rarely perform simultaneous bilateral surgery. The main reason is that it’s thought to raise the risk of bilateral endophthalmitis.

However, in sick neonates with multiple life-threatening comorbidities, the risk of mortality from a second general anesthesia session may be up to 1 million times greater than the risk of bilateral endophthalmitis.5 Immediate sequential bilateral vitreoretinal surgery may sometimes be the best approach for sick children with rapidly progressive bilateral disease who are at risk for anesthesia-related complications and for whom a second surgery may not be possible.5

Counseling and follow-up

Parents and caregivers are essential partners in the healing process. The success of the surgery depends on their ability to keep appointments, apply eye drops or ointments, and maintain positioning if necessary.

This can be overwhelming for families as their child may be following up with multiple subspecialists. It’s also important to clearly communicate the goals of surgery, especially if the visual potential is limited and the primary goal is to salvage the globe. Monocular situations are common, and appropriate precautions and counseling are important to ensure the fellow eye is protected. For most conditions, life-long monitoring is recommended.

Bottom line

The optimal management of pediatric retinal detachments requires a nuanced approach that stems from differences in their presentation, etiology and overall treatment paradigms. The five main lessons from this article are:

- Use scleral buckles for RRDs.

- Release the traction and avoid iatrogenic breaks for TRDs.

- Treat the source of exudation for ERDs.

- Partner with the family and clarify treatment goals.

- Think about the whole patient, not just the eye.

By following these basic tenants, we can strive for successful outcomes in the youngest patients. RS

REFERENCES

1. Gan NY, Lam W-C. Retinal detachments in the pediatric population. Taiwan J Ophthalmol. 2018;8:222–236.

2. Nuzzi R, Lavia C, Spinetta R. Paediatric retinal detachment: A review. Int J Ophthalmol 2017;10:1592–1603.

3. Rossin EJ, Tsui I, Wong SC, et al. Traumatic retinal detachment in patients with self-injurious behavior. Ophthalmol Retina. 2021;5:805–814.

4. Starr MR, Boucher N, Sharma C, et al. The state of pediatric retinal detachment surgery in the United States: A nationwide aggregated health record analysis. Retina 2023;43:717-722.

5. Yonekawa Y, Wu W-C, Kusaka S, et al. Immediate sequential bilateral pediatric vitreoretinal surgery: An international multicenter study. Ophthalmology 2016;123:1802–1808.

6. Yonekawa Y, Fine HF. Practical pearls in pediatric vitreoretinal surgery. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers Imaging Retina. 2018;49:561–565.