Take-home points

|

|

Bios Dr. Asahi is a vitreoretinal surgery fellow at the Gavin Herbert Eye Institute at the University of California, Irvine. Dr. Kuppermann is the Steinert Endowed Professor and Chair of Ophthalmology at the Gavin Herbert Eye Institute and codirector for the Center for Translational Vision Research. Dr. Mishra is a clinical assistant professor of ophthalmology at the Gavin Herbert Eye Institute. He specializes in vitreoretinal surgery and diseases as well as ocular oncology. DISCLOSURES: Dr. Asahi has no relevant disclosures. Dr. Kuppermann disclosed financial relationships with Allergan/AbbVie, Apellis Pharmaceuticals, Genentech/Roche, Ionis, Iveric Bio, Novartis, Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, RegenXBio, Allegro Ophthalmics, Amgen, Aviceda Therapeutics, Dr. Mishra is a consultant for Bausch + Lomb and RegenxBio. |

Unlike neovascular age-related macular degeneration, no treatment options for geographic atrophy existed until recently. Intravitreal complement inhibitors have demonstrated efficacy in slowing the progression of GA, with two agents in this class approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration—pegcetacoplan (Syfovre, Apellis) and avacincaptad pegol (ACP, Izervay, Iveric Bio/Astellas).

These agents have opened the doors for a new age of management in the GA space. Now, with a large patient class eligible for treatment, retina specialists face previously unanswered questions on patient selection for GA treatment and the risk-benefit profiles of these new agents. Here, we review trial data for these agents and present management pearls for patients with GA.

C3 inhibition

The OAKS and DERBY Phase III trials for pegcetacoplan, a complement factor C3 inhibitor, demonstrated an 18- and 22-percent reduction in GA lesion growth rate over 24 months compared to sham with every-other-month (EOM) and monthly dosing, respectively. The trials included patients with GA lesions with or without subfoveal involvement and excluded patients with choroidal neovascularization in the study eye (fellow-eye CNV wasn’t exclusionary).

The GALE extension study continued to demonstrate increasing treatment effects over a 36-month period, with a 24- and 35-percent reduction in lesion growth rate for EOM and monthly dosing, respectively. This is compared to the projected rate of GA lesion growth in the sham arm, which has been assumed to be linear.

These study findings have also suggested that longer treatment duration is associated with continued divergence in the rates of GA progression between the treatment and sham groups. A post-hoc analysis demonstrated functional benefits with preservation of the mean threshold sensitivity in the perilesional zone and reduction in scotomatous points.1,2 However, the findings showed no statistical differences in vision between treated and sham groups overall.

C5 inhibition

The GATHER1 and GATHER2 pivotal trials for ACP, a complement factor C5 inhibitor, included patients with extrafoveal GA lesions within 1,500 µm of the center point, and excluded patients with CNV in either eye. GATHER1 explored monthly dosing at different doses of ACP and demonstrated a 35-percent reduction in GA lesion growth at 12 months. GATHER2, which focused on the 2-mg dose and then re-randomized participants to monthly or EOM dosing after 12 months of monthly dosing, reported a 17.7-percent reduction in GA lesion growth at 12 months.

Notably, EOM dosing produced a GA growth rate reduction that was similar to monthly dosing: a 14- vs. a 19-percent reduction for monthly vs. EOM dosing. A post-hoc analysis of pooled data from both trials over the first 12 months of treatment found a 56-percent decrease in the risk of persistent vision loss in ACP-treated patients vs. sham, with persistent vision loss defined as a 15-letter decrease in best-corrected visual acuity for any two consecutive visits.3

The 24-month data didn’t reach significance. However, similar to the pivotal trials for pegcetacoplan, the efficacy analysis of the ACP pivotal trials showed no statistical difference in vision between treated and sham groups in the overall study population.

|

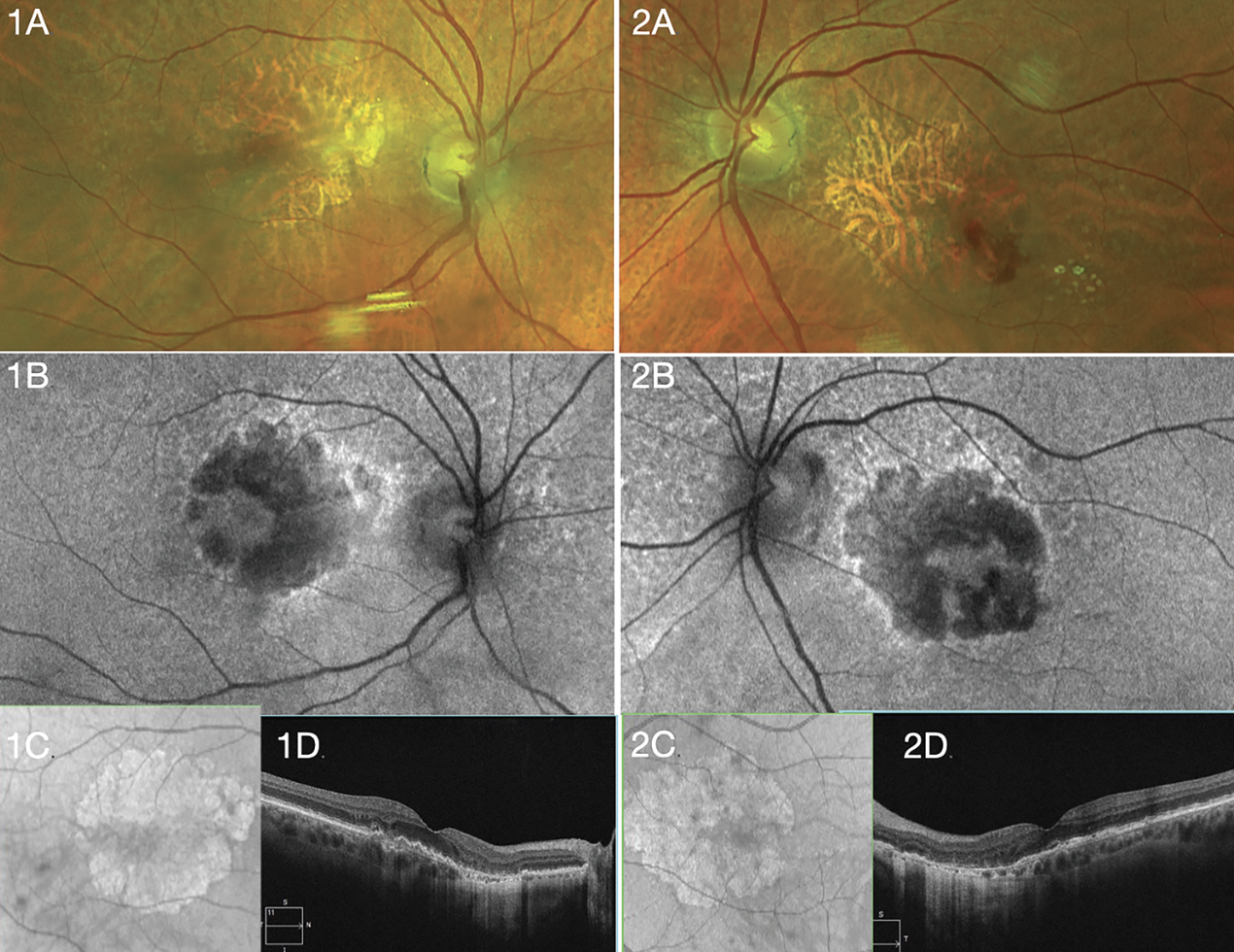

| A 72-year-old Caucasian woman with geographic atrophy in both eyes received treatment for neovascular age-related macular degeneration in the left eye. Vision is 20/20 OD and 20/25 OS. She's considering complement inhibition. Right (1A-D) and left (2A-D) eye show appearance of GA with fundus photos (A), fundus autofluorescence (B), near-infrared en face imag (C) and optical coherence tomography (D). |

Efficacy of complement inhibition

Due to the variance in design between the two trials, it’s difficult to compare the efficacy of the two available agents with trial data alone. A subpopulation analysis aimed to evaluate potential differences in their efficacy.4 The analysis applied the more restrictive enrollment criteria from GATHER2 to the OAKS/DERBY population with propensity score matching of baseline characteristics to select and compare similar patients with nonsubfoveal GA and no CNV in the fellow eye.

The monthly dosing arm had a 30-percent greater reduction in the GA lesion growth rate favoring pegcetacoplan at 12 months. A nonsignificant but numerically greater trend favored EOM pegcetacoplan to monthly ACP. Generalizability is limited by the study design, statistical methodology and small sample size (roughly 50 in each arm). Currently, barring any head-to-head trials, it’s difficult to make any definitive statements about the relative efficacy of the two complement inhibiting agents.

Potential safety concerns

The overall safety profiles of intravitreal C3 and C5 complement inhibition has shown additional risks compared to other intravitreal medications. Three safety concerns have been identified in particular:

nAMD. For pegcetacoplan, the rate of nAMD at 24 months in the OAKS and DERBY trials was 11.9 percent for monthly, 6.7 percent for EOM and 3.1 percent for sham. For ACP, the respective nAMD rates at 24 months in GATHER2 were 7.4, 5 and 5 percent.

|

Ischemic optic neuropathy. ION was seen with pegcetacoplan at rates of 1.7, 0.2 and 0 percent for the respective arms at two years, and one case reported for ACP, which exited the study.

Intraocular inflammation. IOI rates were 4, 2 and <1 percent, respectively, for pegcetacoplan, and one case reported for ACP at two years. The clinical trials for both agents had no reports of retinal vasculitis or vascular occlusive events.1-3 Real-world cases of retinal vasculitis and intraocular inflammation have been reported at higher rates and severities than in the clinical trials. Of the 14 eyes of 13 patient cases in the postmarketing reports of retinal vasculitis after intravitreal pegcetacoplan, 57 percent of eyes had a 3-line decrease and 43 percent had a 6-line decrease in vision from baseline to final follow up. Two eyes were enucleated.

Interestingly, in the trials and in real- world reports, all cases of retinal vasculitis and IOI occurred after the first injection in the first eye. These events haven’t been reported with ACP to date, with the exception of one unusual case of a patient with Stargardt disease who was injected initially with pegcetacoplan in one eye followed four days later by ACP in the fellow eye, with vasculitis occurring subsequently in both eyes.5

In light of these findings, the retina community has expressed varying degrees of enthusiasm for complement inhibition therapy, which has influenced management strategies for using these agents.

Patient selection

Treatment scenarios we may need to consider for GA patients who may qualify for the new complement inhibitors include bilateral GA with preserved vision, presence of concomitant nAMD in one or both eyes, and the monocular patient who has already lost central vision in one eye from GA or advanced nAMD. We must also consider symptoms, visual acuity, age, fellow-eye status, ocular comorbidities and the risk-benefit profile. Patients at the highest risk for progression are ideal candidates for therapy.

Optical coherence tomography biomarkers, such as hyperreflective foci and drusen volume, have been established as strong predictors of GA development.6 The appearance of incomplete retinal pigment epithelium and outer retinal atrophy (iRORA) is a precursor lesion and portends a high risk of developing GA.7 The near-infrared en face imaging can provide information regarding total area of GA lesion, unifocal or multifocal lesions, and their proximity to the fovea.

Fundus autofluorescence can provide similar information and can help identify specific lesion characteristics through distinct patterns of hyperautofluorescence along lesion borders. Multifocal lesions tend to progress more rapidly, and extrafoveal lesions have been shown to progress more rapidly than foveal lesions.8

After GA is identified and diagnosed, central visual function can begin to decline within 2.5 years, with GA developing bilaterally in 65 percent of cases.9–11 Knowing this can help us to identify the patients who may benefit most from treatment.

Counseling patients

Given that these agents didn’t demonstrate a VA benefit in the overall pivotal trial populations, counseling patients before initiating treatment is of utmost importance. Patients who have lost vision in one eye from GA may be more motivated to raise the topic of complement inhibition.

Those with early GA and good vision or a newer diagnosis may need more education to truly understand the commitment to treatment they will be undertaking. Because initiating treatment frequently isn’t urgent, some patients may benefit from photographs taken during serial visits demonstrating GA progression before they start treatment.

Furthermore, no evidence exists of the implications of discontinuing treatment or having intermittent dosing. Before a patient starts treatment, consider the rate of lesion progression, size, whether it’s unifocal or multifocal, and location in relation to the fovea. Follow-up can be shortened to assess more closely the rate of lesion change before deciding on treatment.

The monocular patient who has lost central vision in one eye to either nAMD or GA and is looking to preserve vision in their better eye may be motivated to seek treatment. Given that the inflammatory events occurred with the first injection in all reported cases thus far, one strategy might be to consider treating the worse-seeing eye first.

If no signs of inflammation emerge, treatment might be considered in the better-seeing eye. However, no formal recommendations have been made on how to initiate treatment. Rather, it may be case-specific depending on the patient’s informed decision-making.

Selecting an agent

|

Factors most likely to drive agent selection are the treatment interval, available agents, and the discussion between physician and patient. Regarding dosing, the label for pegcetacoplan allows for every 25 to 60 days, whereas ACP’s label states every 28 days +/- seven days. Less frequent dosing brings a decreased incidence of IOI and nAMD, but that may come at the cost of possibly less favorable reduction in GA lesion growth. Monthly treatment is typically considered in patients at higher risk for vision loss from more rapid GA progression or patients who elect for monthly dosing over EOM.

In the face of concurrent nAMD changes, the provider’s discretion, as well as healthcare system requirements and the patient’s treatment burden, will likely determine treatment with anti-VEGF agents, either during the same-day visit or at another visit.

In the trials, anti-VEGF injection was administered 30 minutes before complement inhibition injection, and only when intraocular pressure was <21 mmHg.12 We’ve found that many clinicians elect to treat with anti-VEGF and complement inhibition at separate visits. Some manage IOP elevations with topical glaucoma medications or anterior chamber paracentesis.

Bottom line

Factors that guide starting treatment with complement inhibitors for GA include the location, extent and rate of progression of GA lesions, as well as patient age, treatment burden and fellow eye status. The risk-benefit profile of reducing the GA lesion growth rate, nAMD incidence and shared decision-making will inform agent selection and dosing frequency. A trial in the worst eye first may minimize the risk of IOI and vasculitis in the better seeing eye. RS

REFERENCES

1. Heier JS, Lad EM, Holz FG, et al; OAKS and DERBY study investigators. Pegcetacoplan for the treatment of geographic atrophy secondary to age-related macular degeneration (OAKS and DERBY): Two multicentre, randomised, double-masked, sham-controlled, phase 3 trials. Lancet. 2023;402:1434-1448.

2. Wykoff CC, Heier JS, Jones D, Yemanyi F, Nakabayashi M. Long-term efficacy and safety of pegcetacoplan from the GALE open-label extension of the Phase 3 OAKS and DERBY trials. Paper presented at the 2023 American Academy of Ophthalmology Annual Meeting; November 3 to 6, 2023; San Francisco, CA.

3. Jaffe GJ, Westby K, Csaky KG, et al. C5 inhibitor avacincaptad pegol for geographic atrophy due to age-related macular degeneration: A randomized pivotal Phase 2/3 trial. Ophthalmology. 2021;128:576-586.

4. Hahn P et al. Pegcetacoplan vs avacincaptad pegol in patients with geographic atrophy: An anchored matching-adjusted indirect comparison of the Phase 3 trials. Paper presented at American Society of Retina Specialist 41st annual scientific meeting; July 30, 2023; Seattle, WA.

5. Witkin AJ, Jaffe GJ, Srivastava SK, Davis JL, Kim JE. Retinal vasculitis after intravitreal pegcetacoplan: Report from the ASRS Research and Safety in Therapeutics (ReST) Committee. J Vitreoretin Dis. 2023;8:9-20.

6. Regillo CD, Nijm LM, Shechtman DL, et al. Considerations for the identification and management of geographic atrophy: Recommendations from an expert panel. Clin Ophthalmol. 2024;18:325-335.

7. Guymer RH, Rosenfeld PJ, Curcio CA, et al. Incomplete retinal pigment epithelial and outer retinal atrophy in age-related macular degeneration: Classification of Atrophy Meeting Report 4. Ophthalmology. 2020;127:394-409.

8. Fleckenstein M, Mitchell P, Freund KB, et al. The progression of geographic atrophy secondary to age-related macular degeneration. Ophthalmology. 2018;125:369-390.

9. You JI, Kim DG, Yu SY, Kim ES, Kim K. Correlation between topographic progression of geographic atrophy and visual acuity changes. Korean J Ophthalmol. 2021;35:448-454.

10. Heier JS, Pieramici D, Chakravarthy U, et al; Chroma and Spectri Study Investigators. Visual function decline resulting from geographic atrophy: Results from the Chroma and Spectri Phase 3 trials. Ophthalmol Retina. 2020;4:673-688.

11. Lindblad AS, Lloyd PC, Clemons TE, et al; Age-Related Eye Disease Study Research Group. Change in area of geographic atrophy in the Age-Related Eye Disease Study: AREDS report number 26. Arch Ophthalmol. 2009;127:1168-1174.

12. No author listed. Pegcetacoplan (APL-2) Protocol APL2-303; A Phase 3 multi-center, randomized, double-masked, sham-controlled study to compare the efficacy and safety of intravitreal pegcetacoplan therapy with sham injections in patients with geographic atrophy (GA) secondary to age-related macular degeneration (AMD). Apellis Pharmaceuticals; Waltham, MA. August 12, 2020. Available at https://cdn.clinicaltrials.gov/large-docs/00/NCT03525600/Prot_000.pdf.